Casey Research’s Gold Commentary

By Jeff Clark

There are many reasons why gold is still our favorite investment – from inflation fears and sovereign debt concerns to deeper, systemic economic problems. But let’s be honest: it’s been rising for over 11 years now, and only the imprudent would fail to think about when the run might end.

Fortunately, there’s one critical indicator that clearly signals we’re still in a bull market – and further, that we can expect prices to continue to rise. That indicator is negative real interest rates.

The real interest rate is simply the nominal rate minus inflation. For example, if you earn 4% on an interest-bearing investment and inflation is 2%, your real return is +2%. Conversely, if your investment earns 1%, but inflation is 3%, your real rate is -2%.

This calculation is the same regardless of how high either rate might be: a 15% interest rate and 13% inflation still nets you 2%. This is why high interest rates are not necessarily negative for gold; it’s the real rate that impacts what gold will ultimately do.

What History Tells Us

The chart below calculates the real interest rate by extracting annualized inflation from the 10-year Treasury nominal rate. Gray highlighted areas are the periods when the real interest rate was below zero, and as you can see, this is when gold has performed well.

Gold climbs when real interest rates are low or falling, while high or rising real rates negatively impact it. This pattern was true in the 1970s and it’s true today.

A closer study of this chart tells us there’s actually a critical number for real rates that seems to have the most impact on gold. Take a look at how gold performs when real rates are below 2%.

The reason for this phenomenon is straightforward. When real interest rates are at or below zero, cash and debt instruments (like government bonds) cease being effective because the return is lower than inflation. In these cases, the investment is actually losing purchasing power – even with a positive coupon rate. An investor’s interest thus shifts to assets that offer returns above inflation… or at least a vehicle where money doesn’t lose value. Gold is one of the most reliable and proven tools in this scenario.

Politicians in the US, EU, and a range of other countries are keeping interest rates low, which, in spite of a low CPI, pushes real rates below zero. This makes cash and Treasuries guaranteed losers right now. Not only are investors maintaining purchasing power with gold, they’re outpacing most interest-bearing investments due to the rising price of the metal.

Here’s another way to verify this trend. As the following chart shows, from January 1970 through January 1980, gold returned a total of 1,832.6%. This is much higher than inflation during that decade, which totaled 105.8%.

In the current bull market (below), gold has gained 556.3% since 2001, while inflation has thus far totaled 30%.

Further supporting this thesis is the fact that when real rates are positive, gold has not performed well. You can see this in the following chart:

The gold price fluctuated between $300 and $500 for the twenty-year period when rates were positive. This is a strong reminder that bull markets don’t last forever – even golden ones – and that at some point we’ll need to sell to lock in a profit.

So if history demonstrates that gold does well during a negative-rate environment and poorly during positive periods, the natural question becomes…

How Much Longer Will Negative Real Rates Last?

US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated in January that he expects to keep short-term interest rates close to zero “at least through late 2014.” This low-rate, loose-money policy is intended to “support a stronger economic recovery and reduce unemployment.” While his strategy is debatable, this guarantees that if the inflation rate is at all positive, the real rate will be negative – and thus gold will stay in a bull market.

What if the economy improves? After all, there are economic data showing the economy may be finding its footing, making some believe interest rates could be raised earlier, as soon as next year. Based on the data above, the answer to the question is, “What does inflation do?” In other words, interest-rate fluctuations alone aren’t important; it’s how the interest rate interacts with the inflation rate. If inflation simultaneously rises and keeps the real rate negative, we should expect gold to remain in a bull market.

With the obscene amount of money that’s already been printed, high inflation seems almost certain at some point, even if there isn’t any more money creation. This is why we think the end to the gold bull market is not yet in sight.

One more point. You’ll notice in the above charts that this trend doesn’t reverse on a dime. It takes anywhere from months to years for investors to shift from interest-bearing investments to metals – and vice versa. And the longer the trend, the slower the change. Real rates have been negative for a decade now, and with broad institutional investment in gold largely still in absentia, it seems reasonable to expect that the trend in gold won’t shift anytime soon.

Implications for Investors

Armed with these data, there are definite steps you can take with your investments at this point, as well as reasonable expectations you can have going forward:

1. You can buy gold today. As long as real interest rates are negative, gold will remain in a bull market. If you already own some gold, you can and should ask yourself if it’s enough at a time when money in the bank is a losing proposition.

2. Don’t get flummoxed when you hear talk about rising rates. Watch the real rate instead.

3. In our opinion, real rates will be negative for some time for the simple reason that we think inflation will be rising for some time. Ask yourself: Will the Fed and other central banks raise rates aggressively enough to catch up to inflation? Someday, sure… but not anytime soon.

4. When real rates turn positive, especially above 2%, it may be time to sell. We’ll have to see what’s going on in the world at that time; if there’s financial chaos, the fear factor could cause gold to depart from this historic pattern. But even if not, keep in mind that while the price of gold fluctuates every day, the shift out of gold-based investments won’t occur overnight. There should be time to gain clarity.

There are a lot of reasons to own gold today, and there will likely be more before it’s time to say goodbye. In the meantime, we take comfort in the fact that the strongest historical indicator of all tells us the gold bull market is alive and well and has years to play out.

Carpe aurum!

By Peter Schiff

Gold has been holding steady in the the $1,600-$1,800 band since early October. This could be attributed to consolidation after last summer’s historic run up to $1,895, but I think this wait-and-see attitude reflects current market sentiment toward the US dollar.

In fact, the first few days of April have seen a sharp dollar rally and decline in gold. This is rooted in deflated expectations of a third round of Quantitative Easing (QE3) after the most recent Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting. Once again, the markets are responding to the headlines while losing sight of the fundamentals.

This is especially peculiar because the Fed did not explicitly take QE3 off the table. In fact, according to the minutes, if the recovery falters or if inflation is too low, the Fed is already prepared to launch QE3. While there is not much chance of low inflation, I’ll explain below why the recovery is not only going to falter – it’s going to evaporate like the mirage that it is!

Casey Research’s Gold Commentary

By Doug Casey

In an interview with Sr. Editor Louis James, the inimitable Doug Casey throws cold water on those celebrating the economic recovery.

Louis: Hi Doug. I have to say, Doug, the so-called recovery is looking more than “so-called” to a lot of smart folks.

Doug: The first order of business, as usual, is a definition: a depression is a period of time in which the average standard of living declines significantly. I believe that’s what we’re seeing now, whatever the numbers produced by the politicians may seem to tell us.

Louis: I was just shopping for food and noticed that the bargain bread was on sale at 2 for $5. My gas costs almost as much per gallon. That’s got to hurt a lot of people, especially on the lower income rungs. I don’t need to ask; a member of my family just got a job that pays $12 per hour – about three times what I made working for the university food service back when I was in college – and it’s not enough to cover his rent and basic bills. If his wife gets similar work, they’ll make ends meet, but woe unto them if anyone in their family crashes a car or requires serious medical treatment.

Doug: That’s just what I mean. Actually, the trend towards both partners in a marriage having to work really started in the early ’70s – after Nixon cut all links between the dollar and gold in August of ’71. Before then, in the “Leave It to Beaver” era, the average family got by quite well with only the husband working. If he got sick or lost his job, the wife was a financial backup system. Now, if something happens to either one, the family is screwed.

I think, from a very long-term perspective, historians will one day see the ’60s as the peak of American prosperity – certainly relative to the rest of the world… but perhaps even in absolute terms, even taking continued advances in technology into account. Maybe the ’59 Cadillac was the bell ringing at the top of that civilizational market.

My friend Frank Trotter, President of EverBank, was just telling me that the net worth of the median US citizen is only $6,000. That’s the median, meaning that half of the people have less than that. Most people don’t even have enough stashed away to buy the cheapest new car without going into debt. It used to be that people bought cars out of savings, with cash. Now they have to finance them over at least five years… or lease them – which means they never have even that trivial asset, but a liability in the form of a lease.

With the concentration of wealth among the top one percent, most of those below average have seriously negative net worth, at least compared to their earning capacity. In other words, the US, Europe, and other so-called First-World countries are in a wealth-liquidation cycle that will be as profound as it will be protracted.

By that, I mean that people are on average consuming more than they produce. That can only be done by consuming savings or accumulating debt. For a time, this may drive corporate earnings up, and give this dead-man-walking economy the appearance of returning health, but it’s essentially, necessarily, and absolutely unsustainable. This is an illusion of recovery we’re seeing – the result of our Wrong-Way Corrigan politicians continuing to encourage people to do the exact opposite of what they should do.

Louis: Which is?

Doug: Save. People shouldn’t be getting new cars, new TVs, and new clothes. They should be cutting expenses to the bone.

The Obama Administration, just like the Baby Bush Administration before it (there really is no great difference between the Evil Party and the Stupid Party) stubbornly sticks to the bankrupt idea that economic growth is driven by consumption. This is confusing cause and effect. Healthy consumption follows profitable production in excess of consumption, resulting in savings – accumulated capital – that can either be spent without harm or invested in future growth.

Consumption doesn’t cause an economy to grow at all. To paraphrase: “It’s productivity that creates wealth, stupid!”

Louis: Policies aimed at encouraging consumption, instead of increasing production, are what turned the savings rate negative in the US and resulted in the huge sovereign debt issues we’re seeing in supposedly rich countries…

Doug: Well, the governments themselves have spent way more than they had or ever will have, and that’s par for the course when you believe spending is a virtue. However, it’s the false signals government interference sends to the market that caused the huge malinvestments that only began to go into liquidation in 2008. That has to do with another definition of a depression: It’s a period of time when distortions and malinvestments in the economy are cleared.

Unfortunately, that process has barely even started. In fact, since the bailouts began in 2008, these things have gotten much worse. If the government had gone cold turkey back then – cut its spending by at least 50% for openers – and encouraged the public to do the same, the depression would already be over, and we’d be on our way to real prosperity. But they did just the opposite. So we haven’t yet entered the real meat grinder…

Louis: Those false signals the government sends to the market being artificially low interest rates?

Doug: Yes, and Helicopter Ben’s foolish leadership in the wholesale printing of trillions of currency units all around the world – I don’t really want to call dollars, euros, yen, and so forth “money” anymore. When individuals and corporations get those currency units, they think they’re wealthier than they really are and consume accordingly. Worse, those currency units flow first to the state – which feeds its power – and favored corporations, which get to spend it at old values. It’s very corrupting. There is also an ongoing regulatory onslaught – the government has to show it’s “doing something” – which makes it much harder for entrepreneurs to produce.

In addition, keeping interest rates low encourages borrowing and discourages saving – just the opposite of what’s needed. I don’t believe in any state intervention in the economy whatsoever, but in the crisis of the early 1980s, then-Fed Chairman Paul Volcker headed off a depression and set the stage for a strong recovery by keeping rates very high – on the order of 15-18%. They can’t do that now, of course, because with the acknowledged government debt at $16 trillion, those kind of rates would mean $2.5 trillion in annual interest alone – more than the government takes in taxes.

At this point, there’s no way out. And there’s much more tinkering with the system ahead, at the hands of fools who remain convinced they know what they’re doing, regardless of how abject their past failures have been.

Louis: As Bob LeFevre used to say, “Government is a disease masquerading as its own cure.” Want to update us on when you think the economy will return to panic mode?

Doug: Earlier this year, I was expecting it sooner than I do now. Unless some “black swan” event upsets the apple cart suddenly, I would not expect us to exit the eye of the storm at least until after the US presidential elections this fall. Maybe not until early 2013, as the reality of what’s in store sinks in. I pity the poor fool who’s elected president.

In a way, I hope it’s Obama who wins, mainly because the worthless – contemptible, actually – Republican candidates yap on about believing in the free market, which means if one of them is somehow elected, the free market will be blamed for the catastrophe. Too bad Ron Paul will be too old to run in 2016, assuming that we actually have an election then…

Louis: So, what about those numbers, then? Employment is up, and the oxymoronic notion of a “jobless recovery” was one of our criticisms before…

Doug: Yes, but look at the jobs that have been spawned; they are mostly service sector. Such jobs can create wealth for certain individuals – it looks like we’ve put more lawyers to work again, as well as waiters and paper-pushers – but they don’t amount to increased production for the whole economy. They just reshuffle the bits around within the economy.

Louis: Unlike my favorite – mining – which reported 7,000 new jobs in the latest report, if I recall correctly.

Doug: Yes, unlike mining, which was more of an exception than the rule in those numbers. But that’s making the mistake of taking the government at its word on employment figures. If you look at John Williams’ Shadowstats, which show various economic figures as the US government itself used to calculate them, unemployment has actually reached Great Depression levels.

The US government is dishonestly fudging the figures as badly as the Argentine government – which is, justifiably, viewed as an economic laughing stock in most parts of the world. One reason things are going to get much worse in the US is that many of those with economic decision-making power think Argentine President Cristina Fernandez Kirchner is a genius. A little while ago, there was an editorial in the New York Times – the mouthpiece for the establishment – written by someone named Ian Mount.

If you can believe it, the author actually says, “Argentina has regained prosperity thanks to smart economic measures.” The Argentine government “intervened to keep the value of its currency low, which boosts local industry by making Argentina’s exports cheaper abroad while keeping foreign imports expensive. Argentina offers valuable lessons … government spending to promote local industry, pro-job infrastructure programs and unemployment benefits does not turn a country into a kind of Soviet parody.”

When I first read the article, I thought I was reading a parody in The Onion. I love Argentina and spend a lot of time there. It’s a fantastic place to live – but not because of the government’s economic policies!

Fortunately, though, the Argentine government is quite incompetent at people control, unlike the US. It leaves you alone. And there’s a reasonable chance the next president won’t be actively stupid, which isn’t asking much. But it’s amazing that the NYT can advocate Argentine government policy as something the US should follow. A collapse of the US economy would be vastly worse than that of the Argentine economy – the US dollar is the world’s currency.

In Argentina, they’re used to it and prepared for it to a good degree. Very unlike in the US.

Louis: What are the investment implications if the Crash of 2012 gets put off until the end of the year, or even becomes the Crash of 2013?

Doug: There are potentially many, but generally, the appearance of economic activity picking up is bullish for commodities, especially energy and raw materials like industrial metals and lumber. That’s not true for gold and silver, so we might see more weakness in the precious metals in the months ahead. I wouldn’t count on that, however, because government policy is obviously inflationary to anyone with any grasp of sound economics. That will keep many investors on the buy side.

Plus, the central banks of the developing world – China, India, Russia, and many others – are constantly trading their dollars for gold. There are perhaps seven trillion dollars outside the US, and about $600 billion more are sent out each year via the US trade deficit.

Louis: I know I bought some gold and silver in the recent dip and would love to have a chance to do so at even lower prices ahead.

Doug: That’s the logical thing to do, given the fundamental realities we started this conversation with, but a lot of people will be scared into selling if gold does retreat. A good number will sell low, after buying high – happens every time, and is a big part of why commodities have such a tricky reputation.

Most investors just don’t have the strength of conviction to be good speculators. Instead of looking at the world to understand what’s going on and placing intelligent bets on the logical consequences of the trends, they go with the herd, buying when everyone else is buying and selling when everyone else is selling. This inverts the “buy low and sell high” formula. They let their thoughts be influenced by newspapers and the words of government officials.

Louis: In other words, everything you see calls for gold continuing upward for some time – years.

Doug: I look forward to the day when I can sell my gold for quality growth stocks – but we’re nowhere near that point. But silver might correct less than gold if gold corrects due to the appearance of economic recovery – silver is, after all, an industrial metal as well as a monetary one.

Louis: Which leads to the other reason for owning precious metals – not as a speculation on skyrocketing prices, nor as an investment for good yield, but for prudence.

Doug: Yes. Gold remains the only financial asset that is not simultaneously someone else’s liability. Anyone who thinks they have any measure of financial security without owning any gold – especially in the post-2008 world – is either ignorant, naïve, foolish, or all three.

Look, we saw it coming, but everyone in the world could see Humpty Dumpty fall off the wall in 2008. Now we’re just waiting for the crash at the bottom, and no amount of wishful thinking otherwise is going to change that. It’s a truly dangerous world out there, and blue chips are no longer the safe investments they once seemed to be. You don’t have to be a gold bug to see the wisdom of allocating some capital – and not just a token amount – to cover the possibility that I’m right about what’s coming.

There’s some opportunity cost associated with taking out this kind of insurance, but it’s not catastrophic if I’m wrong, and the cost of failing to do so if I’m right is catastrophic. That really is the bottom line.

Louis: Very well. Any particular triggers you think we should watch out for – warning signs that we really are about to exit the eye of the storm?

Doug: In the US, the Fed being forced to raise interest rates would be one, or inflation getting visibly out of control – which would force a change in interest rates – would be another. Who knows – Obama getting reelected could tip the scales. War in the Middle East could do it, or, as we already mentioned, China or Japan going off the deep end. The ways are countless. Black swans the size of pteranodons are circling in squadron strength. A lot of them are coming in for a landing.

People will just have to stay sharp – sorry, there’s no easy way to survive a depression. As my friend Richard Russell says, “In a depression, everybody loses. The winner is the guy who loses the least.” It will take work and diligent attention to what’s going on in the world and around us. We at Casey Research will do our best to help, but each of us is and must be responsible for ourselves.

Louis: Okay then, thanks for the guru update. No offense, but in spite of the investments I’ve made betting that you’re right, I hope you’re wrong, because the Greater Depression is going to destroy many lives, and the famines and wars it spawns even more – millions, I’m sure. Maybe more. The mind balks.

Doug: Oh, I agree. I only wish I could believe otherwise, because I’m sure it’s going to be even worse than I think it will be… although I hope to be watching it in comfort and safety on my widescreen TV, not out my front window.

Mark Motive’s Gold Commentary

After peaking at $1,780 in late February, gold dropped over $100 in March, finishing the month at $1,662.50.

Whenever there is a big move up or down, we all naturally seek confirmation and reassurance of our investment strategy, which is why investors must use objective measures to evaluate and re-evaluate their positions.

As someone who is invested in gold bullion, I enjoy speaking with like-minded people. Many agree that the United States’ massive budget deficits and global monetary inflation support the gold bull market. I don’t see this changing in the near future. Still, sentiment is not enough upon which to rely – I need a yardstick.

For me, that yardstick is US real interest rates. Real interest rates represent the inflation-adjusted interest rate on ‘risk-free’ assets, such as US Treasuries. In other words, if a Treasury bond is held to maturity, the real interest rate shows if the bond investor is losing money due to inflation even if the bond posts a profit.

Calculating Real Interest Rates

There are many variations of this measure, but I use 1-year, constant-maturity US Treasury Bill yields as my starting rate and 1-year US food inflation as the adjustment factor.

Using food as a proxy for inflation is insightful for a few reasons: 1) it’s a good that everyone buys, so it has an impact on most everybody, 2) agricultural commodity price increases are quickly incorporated into consumer food prices, so it’s quick to mirror real world inflation, and 3) the food industry is well-developed, so food prices already incorporate savings gained by large-scale production.

By no means is my methodology the only way to calculate real interest rates. Some investors choose to use longer-dated Treasuries and various other measures of inflation, such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, I don’t use the CPI because I believe it has been heavily manipulated over the years and may not be a fair representation of inflation. For example, the goods and weightings used to calculate CPI have been revised over time based on changing quality and the availability of substitutes. This means that CPI is more of a cost of living measure than a pure price measure.

That said, regardless of the methodology used, most calculations of real interest rates will vary only in magnitude, not direction.

Why Use Real Interest Rates?

Let’s look at 2011 to illustrate how negative real interest rates affect investors. A 1-year US Treasury Bill purchased on the first trading day of 2011 would have earned about 0.29% if held until maturity. Meanwhile, during 2011, US food prices rose a whopping 4.4%. Using my methodology, someone who placed his savings in a 1-year US Treasury Bill at the beginning of 2011 would have lost 4.11% in purchasing power over the course of the year, despite investing in “safe” US government bonds. This is very bullish for gold.

Negative real interest rates are a direct result of the Federal Reserve’s official policy to maintain favorable government borrowing costs: print money to buy Treasuries at artificially low yields and create inflation to allow the Treasury to pay back the debt in cheaper dollars. This is default by stealth and a direct transfer of wealth from savers to borrowers. The common term for this phenomenon is ‘financial repression’.

The chart below shows the US real interest rate over the past 60 years. The shaded areas are periods in which gold experienced a bull market. As you can see, these periods occurred when real interest rates were low or negative and highly volatile. By contrast, the gold bear market of the 1980s and 1990s occurred when real interest rates were higher, positive, and relatively steady. (Prior to the late 1960s, the gold price was still heavily influenced by the Bretton Woods system and gold prices were fairly flat.)

|

| Source: Plan B Economics |

While this does not prove the causality of the relationship, it makes sense intuitively. Gold performs well during periods of negative real interest rates because there are fewer alternatives for investors seeking to preserve capital and purchasing power. If a US Treasury bond provides a negative after-inflation yield, can it still be considered a safe haven? Most sophisticated investors would answer “no,” because it’s a money-loser right out of the gate (and has a lot of downside risk if nominal yields rise).

Additionally, real interest rate volatility implies that investors are uncertain about Treasury prices and future inflation. This could be caused by financial conditions that are strained beyond the realm of the normal business cycle, such as an unresolved global banking crisis or unsustainable debt. We’re facing both of these crises today.

The Big Picture

Even during periods of negative real interest rates, there are times when US Treasuries perform well in comparison to hard assets – usually during short-term periods of financial stress when investors are scrambling. However, under normal conditions, a US Treasury bond can be expected to provide a total return that is close to its coupon rate, which today is below the rate of inflation.

Any investor using real interest rates to gauge the gold bull market must look through short-term fluctuations to see the secular trend. And today – while the US is overloaded with debt and the Federal Reserve is printing money without hesitation – the secular trend of negative real interest rates remains intact.

What does this mean for the current gold bull market? One day, the gold bull market will end, but given the current outlook for continued negative and volatile real interest rates, but the evidence suggests that day is well in the future.

As this fall’s presidential election takes shape as a contest between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, the rhetoric out of both camps is becoming sharper and more ideological. Looking to exploit Governor Romney’s increasingly close association with Wisconsin representative Paul Ryan (who has been mentioned as a potential vice presidential nominee), the President dedicated a lengthy address earlier this week to specifically heap scorn on Ryan’s budget plan (Ryan is the chairman of the House Budget Committee). The attack lines used by the President not only reveal a preview of the fall campaign but also offer a glimpse of Obama’s skewed views of the social and economic history of the United States.

The President laid bare his beliefs that America’s source of economic strength has been her historical embrace of collective action, wealth redistribution, and government policies that have protected workers from the ravages of the wealthy. To reiterate, he was talking about the United States, not Soviet Russia. He asserted that prosperity “grows outward from the middle class” and that it “never trickles down from the success of the wealthy.” Accordingly, he concludes that our recent struggles stem from the Republican-led abandonment of these successful policies.

In reaching these conclusions Obama relies on classic “wet sidewalks cause rain” reasoning, and assumes that an effect can be the father of the cause. But as we debate how to move the American economy out of the rut in which it is trapped, it’s important to know where to put the cart and where the horse.

To illustrate his point, Obama singled out auto pioneer Henry Ford, who famously paid among the highest wages in the world at that time his company began churning out Model T’s. By paying such high wages Obama believes Ford created consumers who could afford to purchase his cars, thereby giving business the ability to grow. Based on this understanding, any program that puts money into the pockets of the average American consumer will be successful in creating growth, especially if those funds can be taxed from the wealthy, who are less likely to spend. Obama argues that Republican proposals that reign in government spending, and cut benefits to the middle or low incomes, are antithetical to this goal.

While it is true that the American middle class rose in tandem with her economic might, it was the success of the country’s industrialists that allowed the middle class to arise. Capitalism unleashed the productive capacity of entrepreneurs and workers, which brought down the cost of goods to the point that high levels of consumption were possible for a wider cross section of individuals. While Henry Ford, as Obama noted, paid his workers well enough to buy Ford cars, those high wages would never have been possible, or his products affordable, if not for the personal innovation he, and other American industrialists, brought to the table in the first place.

The economists that Obama follows believe that business will only create jobs once they know consumers have the money to buy their products. But just as wet sidewalks don’t cause rain, consumption does not lead to production. Rather, production leads to consumption. Something must be produced before it can be consumed.

Human demand is endless and does not need to be stimulated into existence. Suppose you want a new car, but then you lose your job and you decide to forgo the purchase. Has your desire (or demand) for the car lessened as a result of your diminished employment circumstances? If you are like most people, you still desire the car just as much, but you may decide not to buy it because of your reduced income. It’s not that you no longer want the car (if someone offered it to you at 90% below the sticker price, you might still buy it). It’s that you have lost the ability to afford it given its price and your income. The best way to transform demand into consumption is to lower prices to the point where things become affordable. Efficiently operating industries increase supply and bring down prices. This is what Ford did 100 years ago and Steve Jobs did much more recently.

But by introducing revolutionary manufacturing processes for the mass production of low-end vehicles, Ford was able to drastically lower the price of a product (cars) that were previously available only to the wealthy. Ford didn’t create desire to buy cars, that existed independently. But he greatly expanded the quantity of inexpensive cars which allowed that demand to be fulfilled through consumption. In the process he created wealth for himself and his workers (his efficient techniques meant that workers could demand high wages) and higher living standards for society as a whole.

Obama believes that prosperity came only in the 20th century after the government began redistributing wealth from rich people like Henry Ford to the middle and lower classes. He ignores the fact that America’s greatest growth streak occurred in the 19th rather than the 20th century, and that America had become by far the world’s richest nation before any serious wealth redistribution even began.

The unfortunate part for the President is that wealth must first be produced before it can be redistributed. But redistribution always creates disincentives that result in less wealth being created. All societies that have attempted to create wealth through redistribution have failed miserably. This should be obvious to anyone who spends more than a few minutes studying world economic history. But the President is on a mission to get reelected and his ace in the hole is to fan the flames of class warfare. It’s a tried and true political strategy, and he looks ready to ride that hobby horse until it breaks.

This article was revised on March 23, 2012.

Earlier this month, the Department of Labor reported that 227,000 new jobs were added to the economy in February, marking the third consecutive month of positive jobs growth. Many observers have taken the news as evidence that the recovery is underway in earnest, helping send the S&P 500 index to the highest level in nearly five years. However, the very same day, the Commerce Department reported that after surging for much of the last year, the U.S. trade deficit increased to $52.6 billion for January – the largest monthly trade gap since October 2008. This second data point should dampen enthusiasm for the first.

From 2005 through mid-2008, those monthly figures almost always topped $50 or $60 billion, setting a monthly record of $67.3 billion in August 2006. But when the housing and credit markets imploded, attention was focused elsewhere. At that time, I was one of the few economists to raise a red flag about the dangers of growing trade deficits. In any event, the faltering economy took a huge bite out of imports, pushing the trade deficit down 45% in 2009. Even those people who were still paying attention to trade assumed that the problem was solving itself.

However, after reaching a monthly low of $35.7 billion in May of 2009, the trade deficit began to grow again, expanding 31% in 2010 and 12% in 2011. While the $52.6 billion deficit in January is still about 10% below the monthly average seen in 2006-2008, if GDP continues to nominally expand, as many assume it will, we may soon find ourselves in the exact same place in terms of trade that we were before the financial crisis began. That’s not a good place to be.

If the jobs that we have created over the last few years had been productive, our trade deficit would now be shrinking, not growing. But the opposite is happening. These jobs are being created by the expenditure of borrowed money, and are not helping to forge a newer, more competitive economy. In the years before the real estate crash, our economy created millions of jobs in construction, mortgage finance, and real estate sales. But as soon as the bubble burst, those jobs disappeared. Today’s jobs are similarly being built as a consequence of another bubble, this time in government debt. And, likewise, when this bubble bursts they too will vanish.

Throughout much of the last decade, I had continuously warned that the growing trade deficit was an unmistakable sign that the U.S. was on an unsustainable path. To me, monthly gaps of $60 billion simply meant that Americans were going deeper into debt (to the tune of $2,400 per year, per citizen) in order to buy products that we were no longer productive enough to make ourselves. I pointed out that America had become an economic juggernaut in the 19th and 20th centuries on the back of our enormous trade surpluses, which allowed for growing wealth, a stronger currency, and greater economic power abroad. This is exactly what China is doing today. Deficits reverse these benefits. (To learn how China is spending its surplus, see my latest newsletter.)

My critics almost universally dismissed these concerns, typically saying that our trade deficits resulted from our economic strength and that they were a natural consequence of our status at the top of the global food chain. I pointed out that even highly developed, technologically advanced economies still need to pay for their imports with exports of equal value. Instead, all that we have been exporting is debt and inflation.

The financial crisis initiated a painful, but needed, process whereby Americans spent less on imported products while manufacturing more products to send abroad. But the countless government fiscal and monetary stimuli stopped this healing process dead in its tracks. Government borrowing and spending redirected capital back into the unproductive portions of our economy. Health care, education, government, and retail have all expanded in the last few years. But manufacturing has not grown at the pace needed to solve the trade problem. In short, these jobs are creating more consumers and less producers, they are making us poorer rather than richer.

Job creation at home has been like vegetation sprouting along the banks of rivers of stimulus. These artificial channels may help temporarily, but they prevent trees from taking root where they are needed most. Our economy has yet to restructure itself in a healthy manner. The recession should have forced us to address the problem of persistent and enormous trade deficits. We have utterly failed to do this. So while the job numbers look good for now, the pattern is ultimately unsustainable.

The last time the monthly trade deficit was north of $50 billion, the official unemployment rate was under 6% and our labor force was considerably larger. Should this artificial recovery actually return millions of unemployed workers to service-sector employment, our monthly trade deficits could go much higher – perhaps eclipsing the previous records of 2006. It is possible that the annual deficits could top the $1 trillion mark, thereby joining the federal budget deficit in 13-digit territory.

Also, last week, we got news that our fourth quarter current account deficit widened 15% to just over $124 billion. The $500 billion of annual red ink is actually reduced by a $50 billion surplus in investment income (resulting primarily from foreign holdings of low-yielding US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities – however, when interest rates eventually rise, this surplus will quickly turn into a huge deficit). At anything close to a historic average in employment and interest rates, today’s structural imbalances could produce annual current account deficits well north of $1 trillion. As higher interest rates would also swell the federal budget deficit, it is worth asking ourselves how long the world will be willing to finance our multi-trillion dollar deficits?

Back in the late 1980s, when annual trade and budget deficits were but a small fraction of today’s levels, the markets were rightly concerned about America’s ability to sustain its twin deficits. This anxiety helped lead to the stock market crash of 1987. But with the boom of the ’90s, all talk of trade deficits was dropped. Though I spoke out about the danger of having consumption chronically outstripping our productivity, the general feeling of prosperity meant my warnings fell on deaf ears – even as the deficit figures hit all-time record highs. This was a major factor in the economic implosion of 2008. However, even when the imbalance had reared its head, mainstream economics predicted that the economic contraction would slow consumption sufficiently to significantly close the gap. Once again, I took to the airwaves warning that if the government tried to solve the crisis by encouraging consumption instead of production, the trade gap would only get worse – causing a greater crisis in the near future.

The data has proven my point. Just as the prosperity of the ’90s and ’00s blinded us to the coming crisis in ’08, the current talk of recovery is distracting investors, commentators, and even academics from rapidly degrading fundamentals. This course can only lead to a greater crisis, that I have dubbed in my latest book “The Real Crash.”

The Federal Reserve ran another “stress test” on major financial institutions and has determined that 15 of the 19 tested are safe, even in the most extreme circumstances: an unemployment rate of 13%, a 50% decline in stock prices, and a further 21% decline in housing prices. The problem is that the most important factor that will determine these banks’ long-term viability was purposefully overlooked – interest rates.

In the wake of the Credit Crunch, the Fed solved the problem of resetting adjustable-rate mortgages by essentially putting the entire country on an teaser rate. Just like those homeowners who really couldn’t afford their houses, our balance sheet looks fine unless you factor in higher rates. The recent stress tests assume market interest rates stay low, the federal funds rate remains near-zero, and 10-year Treasuries keep below 2%. Why are those safe assumptions? Historic rates have averaged around 6%, a level that would cause every major US bank to fail!

The truth is that higher rates are the biggest threat to the banking system and the Fed knows it. These institutions remain leveraged to the hilt and dependent upon short-term financing to stay afloat. While American families have had to stop paying off one credit card by moving the balance to another one, this behavior continues on Wall Street.

In fact, this gets to the heart of why the Fed is keeping interest rates so low. Despite endorsing phony economic data that shows the US is in recovery, the Fed knows full well that the American economy cannot move forward without its low interest-rate crutches. Ben Bernanke is trying desperately to pretend that he can keep rates low forever, which is why that variable was deliberately left out of the stress tests.

Unfortunately, rates are kept low with money-printing, and those funds are starting to bubble over into consumer prices. Bernanke acknowledged that the price of oil is rising, but said without justification the he expects the price to subside. This shows that Bernanke either doesn’t know or doesn’t care that the real culprit behind rising oil prices is inflation. McDonald’s, meanwhile, is eliminating items from its increasingly unprofitable Dollar Menu. A dollar apparently can’t even buy you a small order of fries anymore.

Unless the Fed expects us to live with steadily increasing prices for basic goods and services, it will eventually be forced to allow interest rates to rise. However, if it does so, it will quickly bankrupt the US Treasury, the banking system, and any Americans left with flexible-rate debt.

That is why the Fed feels it has no choice but to lie about inflation. If it admits inflation exists, then it may be pressured to stop it. However, if it stops the presses, it will bring on the real crash that I have been warning about for the past decade. Just as the Fed’s response to the 2001 crisis led directly to the 2008 crisis, its response to 2008 is leading inevitably to either deep austerity or a currency crisis.

[For more on the crisis ahead, pre-order Peter Schiff’s latest book, The Real Crash, due out in May.]Imagine this scenario:

When the banks fail as a result of higher interest rates, the FDIC will also go bankrupt. Without access to credit, the US Treasury will not be able to bail out the insurance fund – which only contains $9.2 billion as of this writing. So, not only will shareholders and bondholders lose their money next time, but so too will depositors!

Americans are much less self-sufficient than they were in the Great Depression. One only needs to look at Greece to see how a service-based economy deals with this kind of economic collapse – crime, riots, vandalism, and strikes.

There are a few countermeasures left in the government’s arsenal, including selling the nation’s gold, but there comes a point at which the charade can go on no longer. The sharply widening current account deficit shows that we are becoming even more dependent on imports that we cannot afford. Just as homeowners had a good run pulling equity from their overvalued properties, Washington and Wall Street will soon find the music turned off. And there will be no one there to help them clean up the mess left behind.

I propose a new rule of thumb: until true economic growth resumes in the distant future, the fed funds rate should also be used as the “Federal Reserve credibility rate.” We’ll use a scale of 0-20, which is approximately how high rates went under Paul Volcker to restore confidence in the dollar. So, until the end of this crisis, if the fed funds rate is near-zero, all the Fed’s statements, forecasts, and stress tests should be given near-zero credibility. When rates rise to 5%, the Fed’s words can be assumed to be ¼ credible. When they hit 20%, that would be a Fed whose words you could take to the bank – if you can still find one.

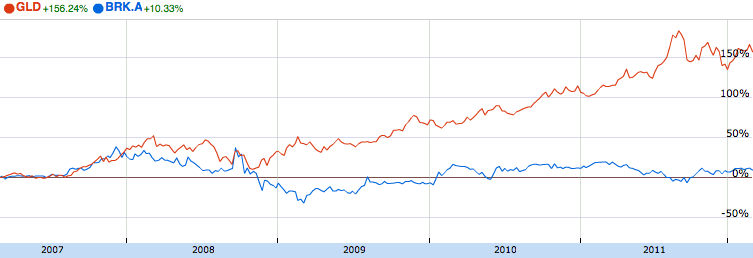

By Peter Schiff

The gold doomsayers have found their champion in the media’s favorite financial advisor and one of the world’s richest men. Warren Buffett, the man dubbed the “Oracle of Omaha,” has repeatedly and publicly denied that gold is an investment, and called gold buyers “speculators” and people “who fear almost all other assets.” In fact, Buffett claims that gold’s rise has the same characteristics as the housing and dot-com bubbles, and it is only a matter of time before it reverses course. He doesn’t mean that the price will decline because of austerity measures and a free-market interest rate, mind you. He just asserts that because he’s deemed it a bubble, it will inevitably burst.

The financial world by-and-large views Buffett as an objective observer, a rare investor who still considers the best interests of common man when he speaks. Each year, there is much hullabaloo over the letter Buffett writes to the shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway. When Buffett makes a claim, the financial world coos and repeats it without question.

The communist revolutions in the 20th century sought to nationalize the wealth generated by privately held industries back to the “exploited” workers on whose backs the profits were supposedly derived. America has made the rejection of this idea and its support of free market principles the centerpiece of its economic narrative. However, as a result of our current and proposed tax policies towards corporate shareholders, our government collects a portion of industrial output that would inspire envy in even the most rabid Bolshevik.

The purpose of a corporation is to generate profits for owners (all other functions are secondary to this goal). Public corporations distribute these profits through dividends. But as a result of America’s system of double taxation, where income is taxed on the corporate level and then again on the personal level, government receives a much bigger share of corporate income than the owners themselves. I also address this topic in my latest video blog.

Suppose a publicly held U.S. corporation made one million dollars in income over the course of a year. Currently its profits would be taxed at a 35% level (for the purpose of this example I will not factor in the lower rate that is applied to its first $100K of profits), meaning that the company would have to pay $350,000 directly to the government (assuming it earned its income without special tax breaks). Of the $650,000 that remained, the typical dividend-paying corporation might distribute 40 percent to shareholders (this is known as the “payout ratio” and the actual average is slightly below 40%). So in this instance the company would pay $260,000 (40% of $650,000) to shareholders. The remaining $390,000 would typically be held as “retained earnings,” and would be used to maintain and replace depreciating equipment, make capital investments, fund research and development, and expand operations. If the company did not make such investments it would be impossible for it to survive and its ability to perpetuate profit distributions would be limited.

These retained earnings still represent assets to shareholders, but their primary purpose is to generate future profits and higher dividends. However, shareholders do not directly benefit from those retained earnings until future distributions are paid. Sure they can sell their shares at a gain, paying a capital gains tax in the process, but this merely transfers those deferred benefits to the new buyer.

When received by shareholders, the $260,000 in dividends are taxed again at a rate of 15 percent (according to current law). As a result, shareholders receive just $221,000 of the million dollar profit. The $39,000 in dividend taxes are added to the $350,000 “off the top” corporate tax to bring the government’s total take of the company’s profits to just a shade under $390,000. In other words the government gets about 75% more cash flow from the company than the actual owners. Looked at in a slightly different way, the government gets about 65% of the non-retained earnings while shareholders, who put up the money and take all the risk, get 35%. Does this seem fair?

This level of taxation puts American corporations at a noticeable disadvantage vis-a-vis companies in the countries against which we are most keenly competing. In China, the slicing of the pie is much more favorable to owners. There, corporations are taxed at a rate of 25% and dividends at 10%. Using these numbers (and the same payout ratio used for the U.S. corporation), the Chinese government gets 51% of distributed corporate profits and shareholders get 49%. In Hong Kong (which is part of Communist China), the situation is even better. There, the corporate tax rate is 16% and the personal dividend rate is zero. If you do the math there, the government gets 33% and the shareholders get 67%.

This comparison raises an interesting point. If shareholders in communist China are allowed to keep more of their earnings than shareholders in capitalist America, which nation is more communist and which more capitalist?

Late last month the Obama Administration and Mitt Romney offered competing proposals on corporate tax reform that both politicians say would make U.S. corporations more competitive. Romney’s plan lowers the corporate tax rate to 25% while maintaining the dividend tax at 15%. This makes things slightly better, sending 54% of distributed earnings to the government and 46% to shareholders (not quite as generous as Communist China). Not surprisingly however the Obama plan will make things much more difficult.

Although the President proposes lowering the corporate tax rate to 28% he also wants to scrap the dividend tax and instead tax the distributions as ordinary income. In practice, the vast majority of individual recipients of dividends fall into the higher end of the income spectrum. Which means a very large chunk of these dividends will be taxed at the highest personal rate of 39%. But Obama also wants to subject these high earners to a surtax to pay for his health care initiative, which means that many of the recipients will be taxed at a rate of 44% (this also accounts for the phase out of personal deductions for higher earners!) So for these high-income earners, using our current example, the new distribution split with the government under Obama’s proposals will be about 70/30 in favor of the government. This is actually worse than the status quo.

But it’s actually much worse than that. The corporate income tax is just one of the veins that corporations open for government. Think about all the other taxes that corporations pay, such as the payroll taxes and sales taxes. Sure they pass those taxes on to their employees and customers, but the revenue flows 100% to the government with shareholders getting nothing but a bill for the cost of collection.

Then there are all of the taxes paid directly by the employees themselves on their wages and salaries. Sure, this money belongs to employees and not shareholders, but if not for the profit-making activities of corporations, those wages and salaries, and resulting taxes, could not have been paid. And while employees derive benefits from those after tax distributions too, shareholders get nothing. When all of these channels are factored in, think about how much more the government derives in taxes from corporate activity than its owners receive in dividends. Who knows how high this figure is, but I’m sure the government’s take is many multiples of what shareholders receive.

Back in the 19th Century, America really was a capitalist country. We had no corporate tax and no personal income tax. Shareholders got 100% of distributed corporate income. As a result of this structure, U.S. corporations grew rapidly and helped spark the fastest economic expansion the world had ever seen. But that was then, this is now.

Given the current numbers, even if our leaders were dyed-in-the-wool Marxists, what would be their motivation to nationalize Fortune 500 companies? If they already receive the lion’s share of profit distributions, what would be the point? Such a move risks upsetting the management structures and destroying the remaining profit motive. It would risk killing the goose that lays the golden egg. If government nationalized a company, it would also have to manage it. Does anyone think bureaucrats would make better decisions than private owners? What’s worse, if those decisions produced losses rather than profits, the government would have to absorb them. Under the current systems, the government gets the lion’s share of the profits, but private shareholders are stuck with 100% of the losses.

There is actually a name for our present system: fascism. While fascism and communism are both forms of socialism, at least the fascists are smart enough to know that if the means of production are nationalized, employees and owners won’t work as hard, and the government will lose revenue.

It’s a shame that the country that was once the beacon of freedom and economic liberty no longer has the ability to recognize what capitalism actually looks like. Unless corporate owners are appropriately rewarded for their risks, U.S. corporations will not regain their lost dominance, Americans will not regain their lost liberty, and our standard of living will continue to fall. As it stands now, the United States has become a people of the government, by the government and, most importantly, for the government.

This month, as unleaded gasoline prices increased for 17 consecutive days (to a national average of $3.647 per gallon – up 11% thus far this year) and West Texas Intermediate crude joined Brent crude in breaking through a $100 per barrel level, energy prices emerged as a full blown political issue. While President Obama conveniently claimed that rising prices were the consequence of an improving economy (they’re not, and it isn’t) Republican fingers began to point sanctimoniously at current drilling policies. And while none of the accusers had any idea why prices were actually going up, the award for the most dangerous ‘solution’ must go to Bill O’Reilly at Fox News. The master of the “No Spin Zone” announced that high pump prices could be permanently brought down by a presidential order to restrict exports of refined gasoline. Not only does Mr. O’Reilly’s idea demonstrate contempt for the U.S. Constitution but it also displays a thorough lack of economic understanding.

Oil and gas prices are high now for a very simple reason: the U.S. Federal Reserve has gone on an unapologetic campaign to push up inflation and push down the value of the U.S. dollar. Just last week on CNBC James Bullard, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated this unequivocally. What is somewhat overlooked is the degree to which an inflationary policy at home creates inflation abroad. Many countries who peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar need to follow suit with the Fed. As China, for example, prints yuan to keep it from appreciating against the dollar, prices rise in China. This is especially true for commodities like crude oil.

Many critics, such as Mr. O’Reilly, have relied on a limited understanding of the supply/demand dynamic to question why gas prices are currently so high at home. With domestic gasoline production at a multi-year high and domestic demand at a multi-year low, he logically expects low prices. But he fails to grasp the fact that the price of gasoline is set internationally and that U.S. factors are only a component.

O’Reilly’s loudly proclaimed solution is to limit the ability of U.S. refiners (and drillers) to export production abroad. If the energy stays at home, he argues, the increased supply would push down prices. Although O’Reilly professes to be a believer in free markets he argues that oil (and gasoline by extension) is really a natural resource that doesn’t belong to the energy companies, but to the “folks” on Main Street. What good would “drill baby drill” do for us, he argues, if all the production is simply shipped to China?

First off, the U.S. government has no authority whatsoever to determine to whom a company may or may not sell. This concept should be absolutely clear to anyone with at least a casual allegiance to free markets. In particular, the U.S. Constitution makes it explicit that export duties are prohibited. Furthermore, energy extracted from the ground, and produced by a private enterprise, is no more a public good than a chest of drawers that has been manufactured from a tree that grows on U.S soil. Frankly, this point from Mr. O’Reilly comes straight out of the Marxist handbook and in many ways mirrors the sentiments that have been championed by the Occupy Wall Street movement. When such ideas come from the supposed “right,” we should be very concerned.

But apart from the Constitutional and ideological concerns, the idea simply makes no economic sense.

In 2011 the United States ran a trade deficit of $558 billion. For now at least America has been able to reap huge benefits from the willingness of foreign producers to export to the U.S. without equal amounts of imports. China supplies us with low priced consumer goods and Saudi Arabia sells us vast quantities of oil. In return they take U.S. IOUs. Without their largesse, domestic prices for consumers would be much higher. How long they will continue to extend credit is anybody’s guess, but shutting off the spigots of one of our most valuable exports won’t help.

In recent years petroleum has become an increasingly large component of U.S. exports, partially filling the void left by our manufacturing output. According to the IMF, the U.S. exported $10.3 billion of oil products in 2001. By 2011, this figure had jumped nearly seven fold to more than $70 billion. How would our trading partners respond if we decided to deny them our gasoline?

Keeping more gasoline at home could hold down prices temporarily, but how much better off would the “folks” be if all the prices of Chinese made goods at Wal-Mart suddenly went up, or if such products completely disappeared from our shelves because the Chinese government decided to ban exports that they declared “belonged to the Chinese people?” What would happen to the price of energy here if Saudi Arabia made a similar decision with respect to their oil?

But most importantly, limiting the ability of U.S. energy companies to export abroad will do absolutely nothing to improve the American economy. As a result of our diminished purchasing power, American demand for oil has declined in relation to the growing demand abroad. Consequently, we are buying a continually lower percentage of the world’s energy output. Consumers in emerging markets can now afford to buy some of the production that used to be snapped up by Americans. If U.S. suppliers were limited to domestic customers, then prices could drop temporarily. But what would happen then?

With the U.S. adopting a protectionist stance, and with gasoline prices in the U.S. lower than in other parts of the world, less overseas crude would be sent to American refineries. At the same time lower prices at home would constrict profits for domestic suppliers who would then scale back production (and lay off workers). The resulting decrease in supply would send prices right back up, potentially higher than before. The only change would be that we would have hamstrung one of our few viable industrial sectors. (For more about how diminishing supplies could exert upward pressures on a variety of energy products, please see the article in the latest edition of my Global Investor newsletter).

Mr. O’Reilly can spin this any way he wants it, but he is dead wrong on this point. It is surprising to me that such comments have not sparked greater outrage from the usual mainstream defenders of the free market. To an extent that very few appreciate, America derives a great deal of benefits from the current globalization of trade. Sparking a trade war now would severely reduce our already falling living standards. And given our weak position with respect to our trading partners, such a provocation may be the ultimate example of bringing a knife to a gun fight.

Rather than bashing oil companies, O’Reilly, as well as other frustrated American motorists, should direct their anger at Washington. That is because higher gasoline prices are really a Federal tax in disguise. The government’s enormous deficit is financed largely by bonds that are sold to the Federal Reserve, which pays for them with newly printed money. Those excess dollars are sent abroad where they help to bid oil prices higher.

For years, mainstream economists argued that as long as unemployment remained high, the Fed could print as much money as it wanted without worrying about inflation. The argument was that the reduction in demand that results from unemployment would limit the ability of business to raise prices. However, what those economists overlooked was the simultaneous reduction in domestic supply that results from a weaker dollar (the consequence of printing money).

I have long argued that neither recession nor high unemployment would protect us from inflation. If demand falls, but supply falls faster, prices will rise. That is exactly what is happening with gas. The same dynamic is already evident in the airline industry. Fewer people are flying, but prices keep rising because airlines have responded to declining demand by reducing capacity. Since seats are disappearing faster than passengers, airlines can raise prices. At some point Americans will be complaining about soaring food prices as much more of what American farmers produce ends up on Chinese dinner tables. Because the Fed is likely to continue monetizing huge budget deficits, Americans are going to be consuming a lot less of everything, and paying a lot more for those few things they can still afford.

For full access to the March 2012 edition of the Global Investor Newsletter, click here.